There is a growing body of work aimed at quantifying listening effort using behavioral, physiological, and subjective measures (see McGarrigle et al. Accordingly, tasks designed to vary listening effort may offer insight into age-related performance differences. 2009 Gosselin & Gagné 2011 Desjardins & Doherty 2013 Degeest et al.

That is, older adults appear to dedicate a greater portion of their finite cognitive resources to the speech recognition task compared to younger adults ( Tun et al. Regardless of the specific causes, existing data suggest that age-related declines in degraded speech recognition are likely to place greater demand on cognitive processing. It has also been suggested that some older adults have difficulty tracking dynamic spectral cues, including formant transitions (e.g., Schvartz-Leyzac & Chatterjee 2015 Souza et al. For example, the ability to perceive temporal cues declines with age, even in older adults with audiometrically normal hearing (e.g., Füllgrabe et al. It is probable that one source of such differences is a decline in supra-threshold auditory processing. 1995 Gordon-Salant & Fitzgibbons 1997 Dubno & Ahlstrom 1997). Older adults have even more difficulty recognition speech in degraded listening situations, including those in which the signal is degraded by competing noise ( Füllgrabe et al. Declines in audibility have been strongly linked to poorer speech perception in quiet ( Humes & Roberts 1990). Advancing age results in declines in sensory acuity, supra-threshold sensory processing, and cognitive function, all of which interferes with speech recognition. There has been recent interest in understanding how listening effort is related to the speech-recognition difficulties demonstrated by many older listeners. For convenience, we will utilize the term listening effort here. These concepts are an emerging source of discussion among researchers. 2011) and/or to fatigue (e.g., McGarrigle et al. Broader views of this process have also conceptualized the allocation of resources as related to cognitive spare capacity (e.g., Rönnberg et al. 2000 Desjardins & Doherty 2013 Pals et al.

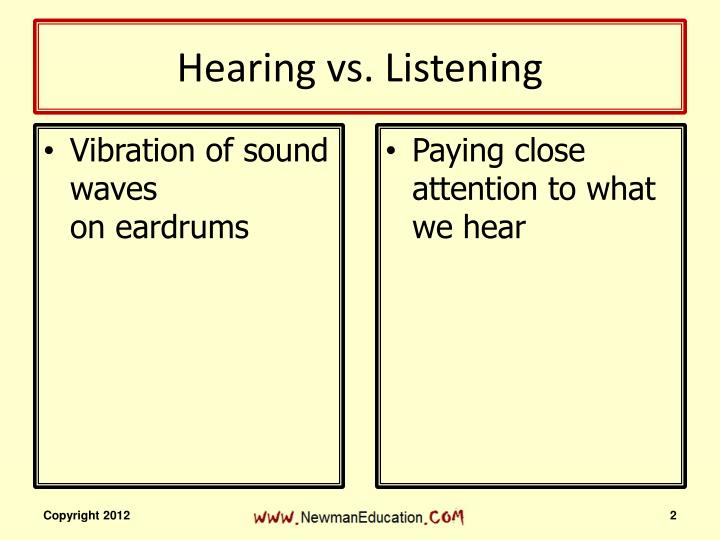

It is thought that listeners experience minimal listening effort in ideal listening conditions and greater listening effort in degraded listening conditions (e.g., Gordon-Salant & Fitzgibbons 1997 Eisenberg et al. The extent to which listeners allocate cognitive resources for speech recognition has previously been referred to as listening effort (e.g., Hicks & Tharpe 2002 Fraser et al.

1996 Rönnberg et al., 2013 Sarampalis et al. As the acoustic signal and/or its internal representation is degraded by signal processing, background noise, hearing loss, or a combination of these factors, there is a concomitant increase in the demand for top-down cognitive processes necessary for speech recognition (e.g., Broadbent 1958 Rabbitt 1966 Downs & Crum 1978 Rakerd et al. Under ideal listening conditions in listeners with normal hearing, this process is largely automatic because the high-fidelity, bottom-up representation of speech is easily matched to the long-term representations of the listener’s native language. To understand speech, a listener must match incoming acoustic information with their internal lexical representation.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)